THERE IS NO SPOON It's interesting to think of economics as a chaotic systems, but I'm not fully convinced of that view by him. Economists say "maybe?" One does need to factor in that chaos theory undermines finance and economics. I think what he calls "theory of narrative" is something that might still be a predictor of market movements, namely good 'ol market sentiment. Especially in this digital age of market manipulation being easy for whoever got in early enough, it might be interesting to figure out "real" (as in human) and "fake" (as in by bots and shills) sentiment and use that to see where markets might be going soon. Greater fool theory rests upon sentiment, doesn't it? edit: also, I've been learning some more about scifi, is Cixin a good place to start?Because The Answer does not exist in the past. The Answer — which is another word for algorithm, which is another word for “general closed-end solution” — doesn’t exist at all in a chaotic Three-Body System.

He's not arguing chaos- far from it. He's saying that the system is impossible to derive algorithmically but possible to model computationally. That's the argument he's making with that whole three body problem thing: we've been using computation to attempt to derive the underlying algorithms at play when it probably isn't possible. However, integrating by parts might not only give you enough of a prediction to profit off of, it might give you better answers than the system can absorb without massive change. Primarily he's arguing that we're trying to algorithmically model something that can't be modeled, and that the way forward is to look at the problem in a completely different way.

Is he not arguing that deterministic chaos is the underlying reason for this? The part I quoted literally has him talking about The Algorithm not existing a chaotic system. To quote wiki (emphasis mine): I think that's what the Three Body Problem is about: From here. So I'd say Ben's argument is "the system is chaotic (=non-algorithmical) but deterministic (=computable) so there is no algorithm that can accurately predict the future, but we can probably predict the next minute by throwing truckloads of data at the problem."Primarily he's arguing that we're trying to algorithmically model something that can't be modeled, and that the way forward is to look at the problem in a completely different way.

Small differences in initial conditions (such as those due to rounding errors in numerical computation) yield widely diverging outcomes for such dynamical systems—a response popularly referred to as the butterfly effect—rendering long-term prediction of their behavior impossible in general. This happens even though these systems are deterministic, meaning that their future behavior is fully determined by their initial conditions, with no random elements involved. In other words, the deterministic nature of these systems does not make them predictable. This behavior is known as deterministic chaos, or simply chaos. The theory was summarized by Edward Lorenz as: "Chaos: When the present determines the future, but the approximate present does not approximately determine the future."

One of the most famous is the three-body problem. Newton's theory of gravitation provides a simple solution to the problem of two mutually attracting bodies, for example the sun and one of its planets. However, as soon as a third body comes into play, for example another planet, the problem becomes mathematically unsolvable. [...] This is no longer true in the three-body problem. A tiny change in one of the variables, for example the speed of the planet Venus, might result in a totally different outcome, for example the planet Mars crashing into the sun. This is called "sensitive dependence on initial conditions".

We're far afield from my known space, but I've always understood chaos and chaotic systems to be those wherein the dynamics are exquisitely sensitive to initial condidtions. Weather, for example: wherever your model starts, your ability to predict at any increment forward depends on the size of the increment. The principle characteristic of chaotic systems is the unpredictability of the change. Chaos theory begins at Poincare, and Poincare begat chaos theory at the three body problem, but does the three body problem exemplify chaos? For purposes of the (tortured) metaphor here, the argument is that a solution to a three-body problem can be brute-forced it just can't be derived. In a way, it's an argument against black swan theory: stuff arises that you can't predict but with a tight enough model you might be able to see it coming, and I think that's the revolution Hunt is alleging. Fundamentally, I think we agree. Fundamentally, though, your understanding of chaos theory is more accurate and nuanced than mine or the author's. ;-)

Same! It's hard to convey uncertainty in writing, so consider this a blanket statement for my position. We agree on what chaos means, although we use different approaches. The econ paper I mentioned also uses "SDIC", sensitive dependence on initial conditions, as their definition of chaos. As an example, if you were to make the smallest possible change to the initial conditions, the effect of that change on the system must grow if time grows. So in a chaotic system, one begets the other: if something is SDIC, then it must also be unpredictably unpredictable. I dug up that econ paper, which is from 1997. Their conclusion is that there's some interesting theories about chaos in markets, but that the indicators of chaos used up until then aren't good enough at separating chaos from regular noise and that the datasets are too small. The only interesting followup study I found looked at the Euro/Dollar market in 2012, and it rejects chaotic behaviour. Personally I think the problem with chaos is that it is too difficult to empirically prove, which is why it seems to be largely ignored by econometrics and economists. With that out of the way, I think there are a bunch of interesting questions Ben doesn't answer satisfactorily (which was the point of my earlier post.) Assuming that all markets are to some degree chaotic, what do we do with that information? I mean, if infinitely small initial conditions can throw an entire system into a change, what does that mean for predictions? Historic analysis is then useless, but I don't know any other means of creating market behaviour theories. His narrative approach sounds interesting but I can't distinguish it from what I know about (market) sentiment. What I think he's aiming for is a non-human-centered approach. Maybe instead of looking at the activity of whales in crypto and following in their footstep by buying/selling alongside them, you could let a computer decide on market movements and whether buying or selling will lead to more or less money. Both examples sound like sentiment and like "narrative" to me. Another thing I wonder is why Ben seems so sure that this isn't being done already. I mean, did you read Lewis' Flash Boys? Besides ML-vagueness, I wouldn't be surprised if high-frequency trading bots use minute-to-minute indicators to predict the next minute. They probably don't make on the fly assessments on whether Germany's bonds are good ones or bad ones, they probably make hundreds of estimates of whether this market will go further up or down if they have been going up or down. It's the inertia they're making money on, I think. The nugget of Ben's writeup, at least to me, is that there's a good argument to make for throwing out all of our economics-related social constructs. Yield spread? Doesn't say shit. Quality? Nope. Death to the KPI, long live computations.We're far afield from my known space

Well, yeah. He's high on his own supply. Start with the derivative-trading bees and work your way down the turtles. FUD it up good and proper, obviously. He's big on "everything you know about money and economics is wrong" which is why he focuses so much on "The Narrative Machine", the one column of his he invariably links in all other columns. Maybe two years, maybe three, I posted a graphic from Epsilon Theory that was out of some big deterministic bit of software that costs a lot of money. It was comically complex and looked a lot like what a wordmap of the Wall Street Journal would look like if assembled for Kabbalistic purposes. As I recall, you dug into it and observed that it was truly a garbage-in, garbage-out tool and that Mr. Rich Ph.D had shoveled a stable-ful of dung into the processor. I think he doesn't care. I think he cares far more about the implications of things rubbing together than he does about how they do it. I think he often loses the trees for the forest; however, he spends a lot of time in different forests than myself so I always read his screeds. And I reckon that if you told him that, he'd say you got the point.With that out of the way, I think there are a bunch of interesting questions Ben doesn't answer satisfactorily (which was the point of my earlier post.)

Assuming that all markets are to some degree chaotic, what do we do with that information?

Another thing I wonder is why Ben seems so sure that this isn't being done already.

The nugget of Ben's writeup, at least to me, is that there's a good argument to make for throwing out all of our economics-related social constructs. Yield spread? Doesn't say shit. Quality? Nope. Death to the KPI, long live computations.

Found it by digging through your #economics posts! 'Twas a mere 400 days ago: I can see that, but it's not very convincing to people not named Ben Thompson. The difference between him writing as Hermit the Blog or as a Bloomberg pundit is not much more than a sense of reality, I think.I think he doesn't care. I think he cares far more about the implications of things rubbing together than he does about how they do it. I think he often loses the trees for the forest; however, he spends a lot of time in different forests than myself so I always read his screeds.

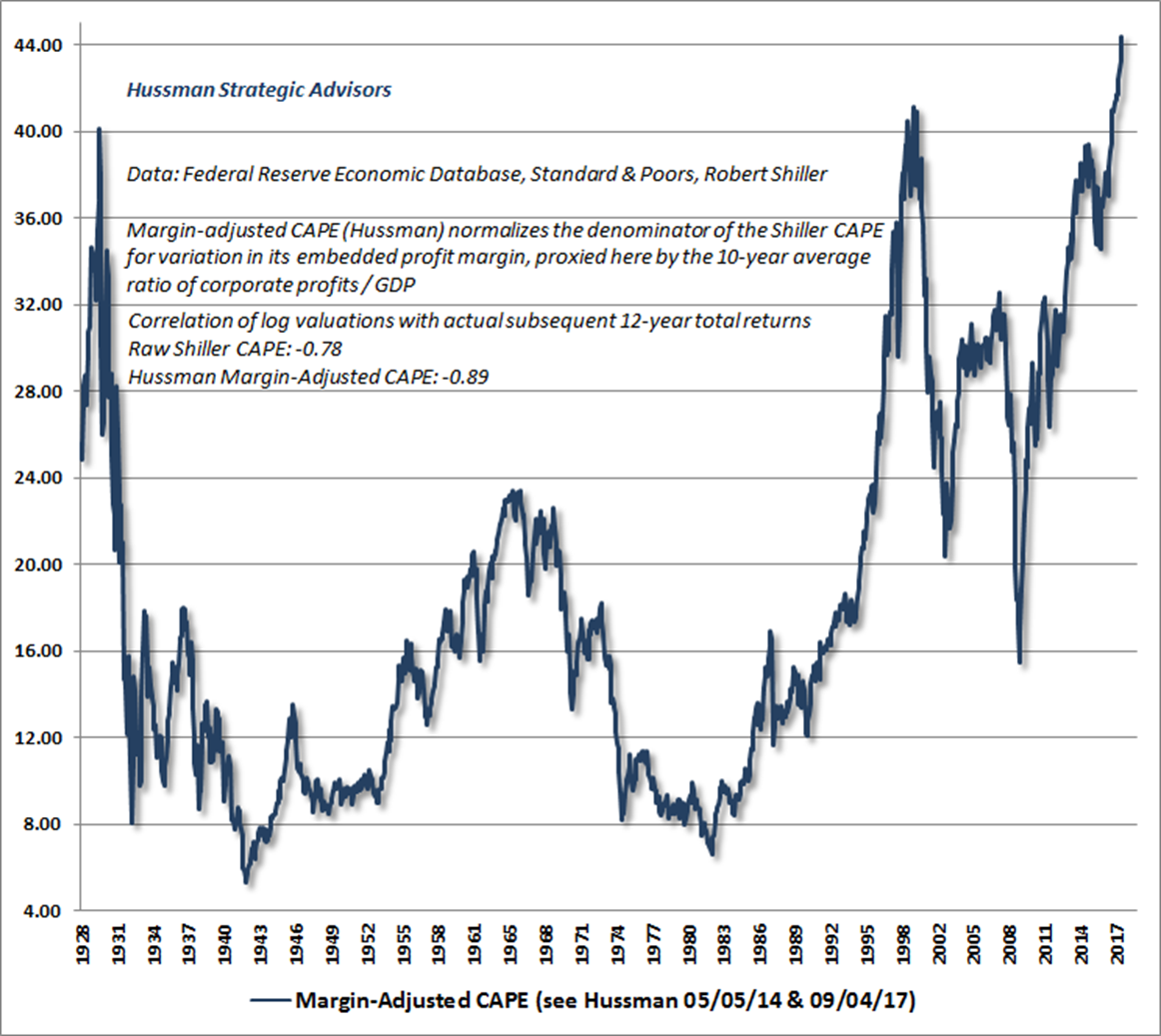

"Hermit the Blog" is an exquisite turn of phrase. Mad props. The thing I like about Ben Rich is he wears his craziness on his sleeve. The rest of them try to act sane. Here's a long, boring treatise on CAPE ratios. I didn't read it. I know about it because this washed over my transom: That's a graph of Steve Hussman's margin-adjusted CAPE, literally a number they synthesized. A measure nobody else uses. They started with CAPE and then tweaked it until it matched better. It's obviously proof of the end-times but not so obviously crazed data-manipulation. They're all manic street preachers. It's refreshing to see one ranting with child-like glee.

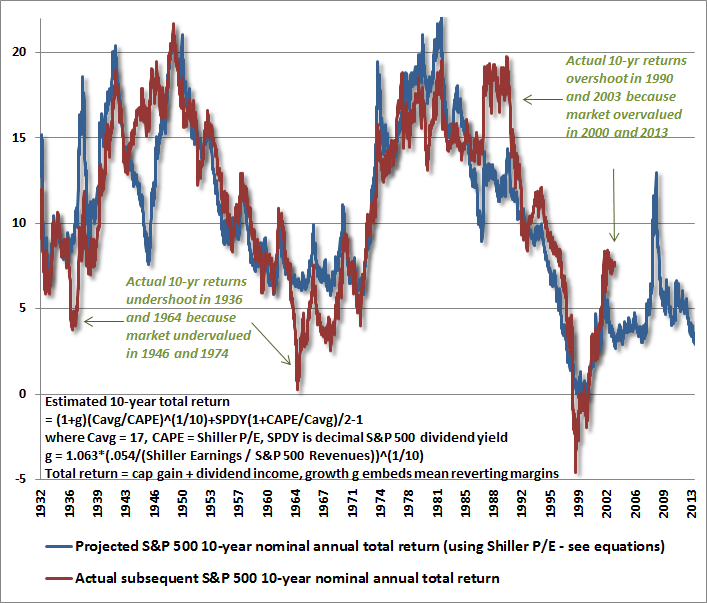

I'll admit, I'm proud of myself for coming up with that one. :) Curiosity got the best of me, so I skimmed the article and did some basic googling. If I understand it correctly they started with a profit over earnings ratio, but used a 10-year earnings average in the denominator which he calls CAPE since it smooths out over cycles. (Was that what he got his Nobel for?!) Hussman then calculates his "CAPEh" in here: If that's par for the course over in Investor Land®, I don't understand how people fall for this crap. Something something fooling some people all of the time...

Dude. Dude. We're talking business majors, that didn't go into accounting, whose primary skill is buying and selling something designed to be bought and sold, whose job it is to predict when things are bought and sold. Remind me - did you read Piketty? Did you notice how every time he resorted to algebra he apologized profusely? Yeah - Schiller got a Nobel for CAPE ratios. Which are literally inflation-adjusted profit-to-earnings. but how are we supposed to do that, egghead? Look at the yearly earning of the S&P 500 for each of the past ten years. Adjust these earnings for inflation, using the CPI (ie: quote each earnings figure in 2017 dollars) Average these values (ie: add them up and divide by ten), giving us e10. Then take the current Price of the S&P 500 and divide by e10. Why ten? Because fuck you, that's why. Anybody in economics serve ten year terms? Anybody in politics? It's too long for tequila and wine, too short for every scotch but one (holy shit: Laphroag is the secret underlying economic research!) and only makes sense in terms of "well, why not ten." But ignore that for a minute. Did you see the part where they explained how to take an average? Do you see that often? The only place I'm used to seeing them explain averages for schlubs who might not remember 5th grade math is economics sites. And then they usually throw some crazy fucking curve up there and start talking about Elliott Wave Theory or some shit. You are now aware that the US Federal Reserve makes most of its predictions and prognostications based on the Phillips Curve. Check out the higher-order math on that guy. I mean, shit. It's got subscripts and superscripts and lambdas and all sorts of crazy mathy stuff but dig into it, and it's basically a bunch of bullshit coefficients having a fight to yield a correlation. Math is like the catalyst in economics. It is essential in order to make it happen but it is neither consumed nor destroyed.To calculate P/E10:

No wonder they see quants/HF traders as earthbound Gods. You'd think there would be a whole school of economics devoted to differential-equations-based modelling, but I can't find much of anything. I have not read Piketty, although I vaguely recall asking you about whether I should read it two, three years ago. You described it as a long and boring economics Powerpoint presentation. Considering I thought Graeber was longwinded, I never attempted Piketty's 25 Hour "..and then there's this graph" Extravaganza. But hey, between then and now I read Zinn and Pinker in less than six weeks, so if you think it can keep me engaged I can give it a shot.

I say do it. You kind of have to let it wash over you - it's a lot less engaging than Zinn or Pinker. I'd put it about on par with Mohammed Said from a prose standpoint and not quite as engaging as Judt. But as you do it, it's kind of a "....well holy shit" experience.