- The real reason so many companies are sick, as Bloomberg explained in a recent feature, has to do with debt. Private equity firms purchased numerous chain retailers over the past decade, loading them up with unsustainable debt payments as part of a disastrous business strategy.

Billions of dollars of this debt comes due in the next few years. “If today is considered a retail apocalypse,” Bloomberg reported, “then what’s coming next could truly be scary.” Eight million American retail workers could see their careers evaporate, not due to technological disruption but a predatory financial scheme. The masters of the universe who devised it, meanwhile, will likely walk away enriched, and policymakers must reckon with how they enabled the carnage.

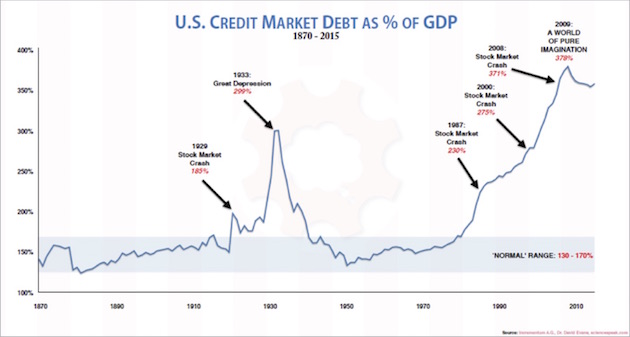

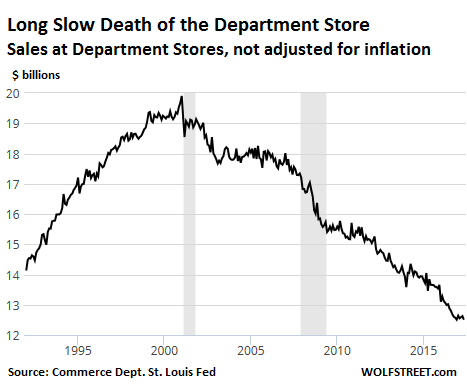

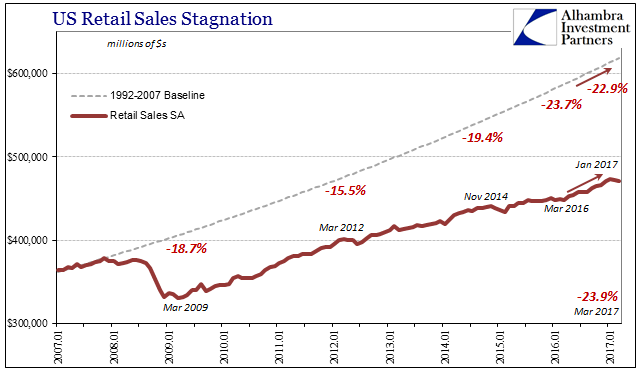

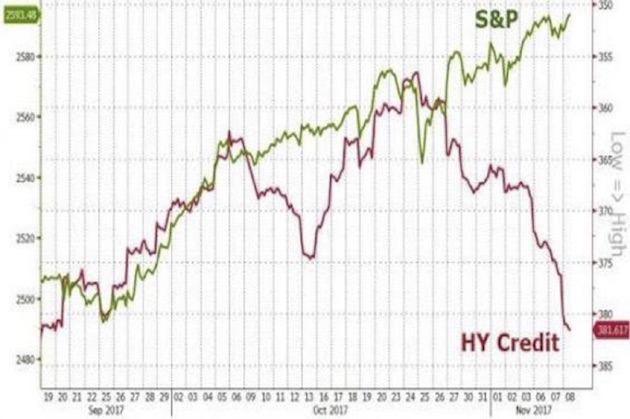

There's some confusion about cause and effect here, as well as some handwaving to discount the very real decline in retail sales. Yeah you called it the "retail apocalypse" just one sentence previously. Nobody is fucking around with that sobriquet. If 4% growth is stagnant than 9% of total sales doesn't get to be an "only." That's not at all what the Bloomberg article says. The Bloomberg article says "oh holy fuck y'all it's about to get hella, hella worse." Wanna see why? The New Republic article actually makes the misunderstanding worse: Bitch please. SO HERE'S THE REAL PROBLEM That scary high-yield credit plummet indicates that investors in the bond market are less and less interested in buying high-yield bonds. Federal interest rates have no direct impact on bond rates; a bond is Toys'R'Us saying "if you lend us x money for y years we'll pay you back z." Considering Toys'r'Us is a lot riskier than a federally-guaranteed loan, you invest with Toys'R'Us because "z" is hella better than what you can get by loaning your money to a bank. It's worth noting that Toys'R'Us couldn't refinance $400m. Argentina oversold $2.75b on a 100 year bond and they default on their debts every 30 years or so on average. In other words, the bond market would rather deal with the return of Pinochet right now than lend money to retail. This, in an environment where: • Bitcoin (which may be worthless) soared nearly 700% from $952 to ~$8000. • The Bank of Japan and the European Central Bank bought $2 trillion of assets. • Global debt rose above $225 trillion to more than 324% of global GDP. • US corporations sold a record $1.75 trillion in bonds. • European high-yield bonds traded at a yield under 2%. • Argentina, a serial defaulter, sold 100-year bonds in an oversubscribed offer. • Illinois, hopelessly insolvent, sold 3.75% bonds to bondholders fighting for allocations. • Global stock market capitalization skyrocketed by $15 trillion to over $85 trillion and a record 113% of global GDP. • The market cap of the FANGs increased by more than $1 trillion. • S&P 500 volatility dropped to 50-year lows and Treasury volatility to 30-year lows. • Money-losing Tesla Inc. sold 5% bonds with no covenants as it burned $4+ billion in cash and produced very few cars. (source) So. The "Retail Apocalypse is happening because nobody is buying anything" but "compared to what we're about to see, maybe we should call the 'retail apocalypse' the 'retail squall' because this:" Is insanity. Ain't nobody out there going "oooooh goody goody! A shuttered Sears to move my new department store into!" A shut Sears is a George Romero film, not a rent-gouging opportunity.This story is at odds with the broader narrative about business in America: The economy is growing, unemployment is low, and consumer confidence is at a decade-long high.

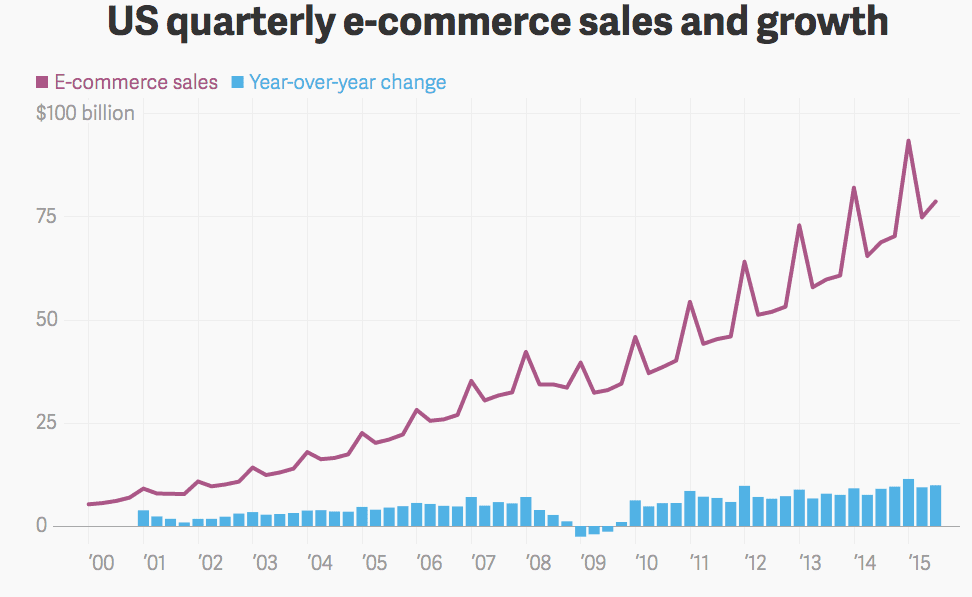

Some point to Amazon and other online retailers for wrestling away market share, but e-commerce sales in the second quarter of 2017 only hit 8.9 percent of total sales. There’s still plenty of opportunity for retail outlets with physical space.

The real reason so many companies are sick, as Bloomberg explained in a recent feature, has to do with debt. Private equity firms purchased numerous chain retailers over the past decade, loading them up with unsustainable debt payments as part of a disastrous business strategy.

Typically retail firms roll over debt to buy time, but interest rates have risen since the last set of buyouts several years ago, making that prospect more expensive.

• A painting (which may be fake) sold for $450 million.

As a shareholder of Seritage, Lampert’s hedge funds can profit from higher rents charged to new retail outlets that move into the shuttered Sears locations.

Riight, so if I understand you correctly this part of the Bloomberg article (which admittedly is better than the one I linked) isn't the big deal, it's this: So is that sentiment, in the current environment, the investor wisdom-of-the-crowd that short-term castle-in-the-sky speculation is the way to go when mid to long-term the shit will hit the fan? The root cause is that many of these long-standing chains are overloaded with debt—often from leveraged buyouts led by private equity firms. There are billions in borrowings on the balance sheets of troubled retailers, and sustaining that load is only going to become harder—even for healthy chains.

Until this year, struggling retailers have largely been able to avoid bankruptcy by refinancing to buy more time. But the market has shifted, with the negative view on retail pushing investors to reconsider lending to them.

Simply put (a retelling of the New Republic article): 1) Large equity firms have been purchasing retail because it's distressed and therefore an opportunity 2) These firms have been financing the operation of retail through high-yield bond issues which have been largely successful because high yield is almost the last game in town where you can make money 3) High-yield bond issues (retail and otherwise) are no longer attractive to investors because, well, because the bond market is starting to see the writing on the wall, frankly 4) Retailers, who like everyone else close out and reissue bonds rather than waiting for them to mature, can't find any buyers for their bonds which means they can't refinance, which means they can't get any more credit, which means they collapse, which means they take down existing bondholders, which means the utter annihilation of disturbing amounts of capital. The fact that it's 2% means that the bond market will pretty much let it happen. The fact that "retail" means "things people buy" means that there will be ripples. UBS has been freaking out about this for two years now: Note that retail is in the noise on that graph. And that graph is two years old. There are two ways to look at this. On the one hand, people have been chicken littling the sky falling for three years now and we're still alive so maybe credit markets are hunky-dory. On the other hand, maybe we've been piling it higher and deeper those past three years so when it crashes, it's gonna be bad.

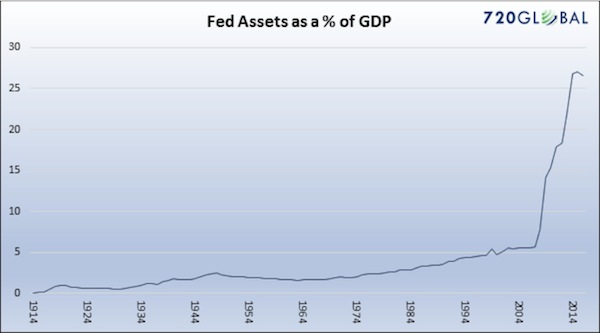

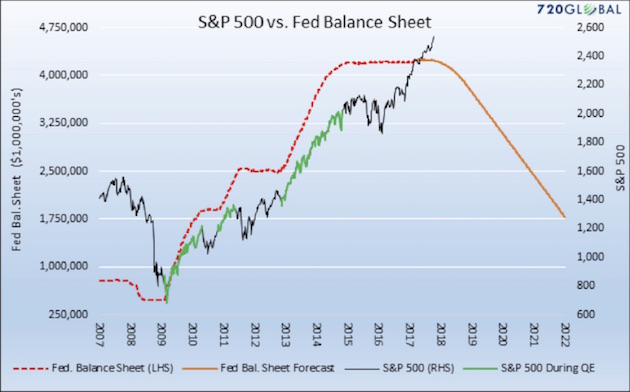

Just to add, because this graph has been much on my mind of late: The wiggly black line is the S&P500. The wiggly green line is the S&P500 on drugs ("quantitative easing" or "the government buys up a bunch of shit so there's money out there"). The dotted orange line tracks how much shit the government has bought up so far; the solid orange line tracks what the Fed has declared they intend to do with all the shit they've bought (dump it like it's on fucking fire). There's two ways of looking at this, too: on the one hand, the S&P is climbing without the government buying it so clearly, the experiment worked. On the other hand, the government hasn't dumped anything since 2008 and when they did, things went really badly so maybe this isn't a great idea hey?

This might be easy to say as someone who doesn't work in retail, but I feel like the disaster isn't the impact to the workers, it's the municipalities left with decaying property values and infrastructure constructed on the premise of supporting business that pays taxes. It all seems to be a positive feedback loop for being awful. A closed anchor store means lousy jobs but also diminishing profits for neighboring stores, limiting their ability to hire the displaced workers and maybe closing shop themselves. The closed businesses lead to lost tax revenue, making it harder for municipalities to maintain the same quality of roads and police, making the area less desirable to customers and new businesses.

I have a semi-related question... I rarely buy products at the "retailers" mentioned in these articles. I generally buy stuff directly from the producer. In fact, I just spent $60 buying Sugru from their web site. It should be here Thursday or Friday. Sugru is also available, and in stock, at the Target store that is 2 miles from my house. But it would NEVER occur to me to purchase it at Target. I want to spend that money with the people who actually make the product. I realize this is true for many of the things I own... the Corbin seat on my motorcycle, the windshield on my motorcycle, my Ernie Ball guitar pedal, the Bongo bluetooth speaker, and my LSTN headphones, and my Native Union bamboo iPhone case. Do I buy Hanes underwear from Target? No. I buy the Duluth Trading Company ones from their web site. Etc, etc, etc. Bear with me... I'm getting to the point... Telephone polls are often quoted as the gospel about how the American public feels. However, telephone polls are ONLY conducted with houses with a landline. I cannot name a single friend of mine who owns a home, and has a landline. Therefore, nobody I know are represented in nationally-quoted phone polls. THE POINT: Is it likely that MY retail purchases - and those retail purchases by other people like me - go completely unrecorded in these graphs you post? How do they track Sugru's sales? Or Native Union? Or Duluth Trading Company? Or are they simply polling Sears and Target and WalMart and extrapolating their numbers from these (flawed and incomplete) data sets?

None of the information here is from polls. It's from SEC information statements and public filings. A privately-held company does not need to disclose revenue and expense information. Try figuring out the profit margins of In'n'Out burger sometime. That said, landline-only polls have been deprecated for the most part. Half of adults don't have one. Pew incorporates landlines at 25%. It does raise an interesting point, though - if you are buying online, you have no real need for Amazon. The only thing Amazon gets you is an ecosystem. If every vendor on the planet had a collective bargaining agreement with shippers and a shared marketplace where you could find their products, nobody would need to bother with Amazon. Which is exactly why Amazon Marketplace exists. As far as retail, don't forget the very real value of showcasing. Not everything can be bought sight-unseen. Not everything comes down to specs and word of mouth. Some stuff you have to see in person before you can buy it, which is a very real reason stores still exist. Walmart is now within a third of a percent of Amazon's prices.

Ok. Right. Private companies do not report their earnings to the SEC, so the only data the SEC has to go on to generate these graphs is by publicly traded companies. So that's less than 4,000 companies, if you take the total number of companies listed on the NYSE and NASDAQ. There are 30 million companies registered in the USA. ~22 million of those are sole proprietorships. That leaves 8 million companies with 2 or more employees. That means payroll, accounting, etc. Going from sole prop to having employees is a HUGE leap, that incurs enormous costs and is not undertaken lightly. So cut that number in half just to cut out the outliers, and you get 4 million companies that have more than one employee, have payroll, corporate taxes, etc. Today, I expect the 4000 listed public companies are worth a large portion of the GDP. But it doesn't take a large increase in sales for 4 million companies to have a major impact on the GDP. And that impact isn't being measured effectively today... so where is the tipping point? Cargill ($120b), Koch Industries ($115b), State Farm ($71b), Albertsons ($58b), Mars ($33b), Publix ($32b), and several other private companies are already making big, significant, needle-moving money, and not reporting it to the SEC.... I wonder where that tipping point is? When does private business become a significant measure, and how do we measure it? As markets move away from the big boxes to more local providers, this could really affect these types of graphs.

Less than 4,000 if you're only talking about retail. Quora thinks 715,000 retail establishments, of which 315k with less than 5 employees so round 'bout 300k retail firms of any size. $3.8T in sales, 15m employees. Not sure what the point is here but there's the numbers.

I'm thinking that the numbers we use to measure the health of our economy are only looking at publicly traded companies. At some point - now? soon? next year? ten years? - publicly traded companies will not be the majority of the economy, and therefore will be poor indicators of America's economic health. In fact, looking at the list of the top 10 privately held companies, I'd argue that we may be at that point now. The US economy is worth about $18 trillion dollars, and privately held companies are worth about $5 trillion today. That means that 27% of our current economic activity is not represented in the graphs you presented earlier in this thread. (And in the data used by economists and government officials to measure the health of the US economy.) How do we improve our measurements and forecasting, if 27% of the money flowing around our economy is not measured/tracked like it is for publicly traded companies? How valuable are our current measurements, and how long can we pretend they are meaningful when they fail to account for such a large portion of our GDP? Not sure what the point is here but there's the numbers.