For me the piece seems a natural companion to the Rushkoff and Lanier books I just finished. Combining the three, I think the core of the matter is this: when you consider the possibilities that both technology and organizational structures allow, the narrow space that tech/business operates in is an abject failure with dire consequences. Rushkoff discusses the problem at length and sees decentralized non-growth systems as a solution, Graeber makes some poignant observations about those consequences and presents ideas for its origin, and Lanier explores the possibilities of how it can be different and why those more humanist alternatives are better. I agree that Graeber fizzles out, which I think is because he bites off a bit more than he could chew with this piece. I haven't read his latest book, perhaps he fleshes his conclusion out more in them. What I am not so sure about is what to do with this information. On the one hand, it seems like we're heading in the right direction with companies wanting to change their structure and practice more and with those new distributed forms gaining some traction. On the other hand, I doubt that change goes fast enough. It's easy to slide into a fatalistic mindset when the problem seems to be so rooted in and fundamental to current society and economies. So I don't know what to think exactly. All three make interesting observations, that's for sure, but I don't see a good way to change the 'lock-in' that's already occurred (to use Laniers term), despite Rushkoffs optimism.

I haven't read any Rushkoff. Should I? I have read Lanier. His basic argument is that technology, for technology's sake, is bad for humanity. Graeber's argument, on the other hand, is "why is there no technology for technology's sake?" on the premise that we were promised technology for technology's sake. Thing is, they're all covering recent history. When you go further back, when you read Tamim Ansary or Jared Diamond or the Durants, you get the perspective that technology is always deployed only when it is beneficial to the deployer. Graeber: So... this is just flat-out wrong. Clearly, nuclear delivery systems were accurate enough to end a world war and even German V-2s were accurate enough to hit "cities." However, by 1948 there was no longer a nuclear monopoly and any attempt to wage remote war at scales that would have led to real loss of life by the direct aggressors would have triggered a massive, expensive, hobbling conflict even back in the early days. As a result, our money went into proxy warfare and ways of influencing world politics in other ways. Graeber again: Assassination is also illegal and an act of war for any signatory of the Geneva Convention. Franz Ferdinand isn't just an indie band and when you attempt to control the world through extrajudicial killing you end up in hot water faster than you can say Anwar Sadat. It's reasonable to argue that our assassination technologies haven't been advancing at blistering pace but it's equally reasonable to argue that they've advanced as fast as we need them to. Remember - it was our failure to kill Osama Bin Laden with cruise missiles that prompted our development of the UAV program... which killed Anwar Al Awlaki just fine. So again, Graeber: I dunno, man. I just found out that one of my old friends' kids has cri du chat syndrome, and thanks to the human genome project they know that the damage done to her genetic code is not in the place that causes mental retardation. I imagine they'd argue that the Human Genome Project has been useful. But it doesn't make big headlines like "death rays" would. So really, Graeber is griping that the future doesn't look the way the pulp sci fi writers said it would, and that's probably a good thing, considering they were one-world-government totalitarians to a man. This precisely maps the explosion of scribes and actuaries under the Ottoman Empire, as well as the legal and clerical classes in Rome. It's almost as if agriculture and civics advances lead to a population explosion who then must be employed so they can eat. Supply and demand in and of itself creates this stuff - the printing press didn't come about until after the Black Death had taken out a third of the population of Europe, thereby putting scribes in high demand. Meanwhile, the Han dynasty had movable type in 1000AD but didn't have the economics to make it worth bothering with. So again, to Graeber: And here I give it over to Petroski - his argument is that we don't have teleportation devices or antigravity shoes is we have no tasks for which the most direct labor-saving device is teleportation or antigravity shoes. Petroski argues (quite convincingly) that necessity is not the mother of invention, luxury is - and that people invent things to make their lives easier, not to make their lives radically different. The Internet is a communications protocol. Cars are faster carriages. There isn't always an obvious precursor - planes are not faster balloons - but balloons got their boost by being movable spy towers that could be deployed easily. Teleportation is a storyteller's conceit, not an engineer's dream and antigravity is nothing more than a fervent wish for the revocation of the physical laws of the universe. Even the most impractical ideas (like the Human Genome Project) have their foundations in practical desires. Which is where I end up handing things over to guys like Bill McKibben and Paul Gilding - who argue that technology is always disruptive and that the exponential growth we've experienced over the past 100 years or so was not the new steady-state, but a discontinuity in an otherwise steady progression of technology. Really, the big thing we did (which none of the guys we've discussed so far have mentioned) is radically increase the availability of energy and for the past ten-twenty years our technological advances have been largely about increasing energy efficiency. It's fair to say that the SR-71, for example, is a pinnacle of Golden Age technology. It's also fair to say that keeping it in the air uses twice as much energy as the Queen Mary. And we've been working on break-even fusion for a long-ass time which is Big Technology in every way Graeber intends but it hasn't paid off... yet. So in the meantime, technological progress has been about doing more with what we have. And damn, I wandered off at the end, too - but fundamentally, I think the argument is not that technology is at a standstill because it doesn't pay off, the argument is technology serves whoever is willing to pay for it and lately, that technology has been serving more boring masters than it did at the height of the Cold War. I'm okay with that.Obviously, there have been advances in military technology in recent decades. One of the reasons we all survived the Cold War is that while nuclear bombs might have worked as advertised, their delivery systems did not; intercontinental ballistic missiles weren’t capable of striking cities, let alone specific targets inside cities, and this fact meant there was little point in launching a nuclear first strike unless you intended to destroy the world.

Contemporary cruise missiles are accurate by comparison. Still, precision weapons never do seem capable of assassinating specific individuals (Saddam, Osama, Qaddafi), even when hundreds are dropped.

Part of the answer has to do with the concentration of resources on a handful of gigantic projects: “big science,” as it has come to be called. The Human Genome Project is often held out as an example. After spending almost three billion dollars and employing thousands of scientists and staff in five different countries, it has mainly served to establish that there isn’t very much to be learned from sequencing genes that’s of much use to anyone else.

In both countries, the last thirty years have seen a veritable explosion of the proportion of working hours spent on administrative tasks at the expense of pretty much everything else. In my own university, for instance, we have more administrators than faculty members, and the faculty members, too, are expected to spend at least as much time on administration as on teaching and research combined. The same is true, more or less, at universities worldwide.

That pretty much answers the question of why we don’t have teleportation devices or antigravity shoes. Common sense suggests that if you want to maximize scientific creativity, you find some bright people, give them the resources they need to pursue whatever idea comes into their heads, and then leave them alone.

Interesting! Trowing Rocks at the Google Bus touches on this but not explicitly. It argues that technology that's good for customers doesn't work in companies dictated by quarterly earnings and shareholders - in other words, not beneficial to them. Put bluntly, the book's two thirds 'here's why growth-based capitalism is bad' and one third 'blockchain and B-corps can save us'. I thought it was a nice read even though he misses the mark sometimes. At the same time I wouldn't be surprised if you can name half a dozen authors who cover the same ground as Rushkoff. I hadn't considered energy efficiency in this way. Something like the steady decline of solar energy costs definitely supports that idea.When you go further back, when you read Tamim Ansary or Jared Diamond or the Durants, you get the perspective that technology is always deployed only when it is beneficial to the deployer.

Bill McKibben has written a few books by now where he lays out, chapter and verse, the idea that Postwar Economic Boom growth was only possible because places that weren't Western Europe and America weren't doing it... and that places like China and India won't ever push that hard into it because the environmental and social costs are too high. He does a pretty good job of arguing that the future is likely to be smaller and more modest and that's just fine because there are plenty of happy people all over the world that don't consume energy at anywhere near the rate we do; he doesn't quite go as far as pointing out that the much reviled hipsters, with their stay-at-home ways and lack of consumption, are the wave of the future but he implies it. I'm halfway to hypothesizing that the difference between an economist and a historian is the historian accounts for externalities. As society integrates globally and it becomes harder and harder to ship your garbage to Somalia, economics becomes a much more social, much more integrated study and energy is neither created nor destroyed.

I'm coming up on one year. :D It's funny that you mention it! I was in the Trump Ovular Office (free grabs, every Tuesday) the other... Wednesday, by, um, invitation. The transcript reads:And we've been working on break-even fusion for a long-ass time...

...that technology has been serving more boring masters than it did at the height of the Cold War.

"am_U, buddy! Hey, the Hydrogen bomb, oh boy. Not good! We could do better, no? I bet, what'dya, with a guy like you? Well no, we could, everyone thinks, and also me too, and you will. Or else, alright, we love ya, kid, now you can solve, so, get it? Do it. So get, go. Get OUT!"

Manhattan 2.0

On the other hand, I saw the best minds of my generation pour their talents into finding eyeballs for ads and and writing bots to trade castles in the air with each other...I think the argument is not that technology is at a standstill because it doesn't pay off, the argument is technology serves whoever is willing to pay for it and lately, that technology has been serving more boring masters than it did at the height of the Cold War.

I'm okay with that.

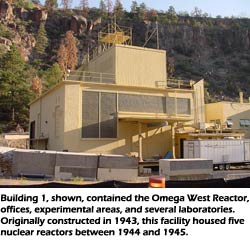

http://3.bp.blogspot.com/-z4PZQkZMMe4/UCuvnzneuzI/AAAAAAAAALk/o2eV5OhaJS0/s1600/IMG_7616%2B%25282%2529.JPG This is a guard tower in my town. During the Reagan years there was a machine gun nest on top. My english teacher, when she was in high school, would stand under it with her girl friends and stage-whisper stuff to each other in Russian to draw the fire of the cute guards who manned it up top. it was all very jocular - "ha ha pretty girl I will fire a .30 carbine over your head to make this exciting." https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/f/f6/Minutemans_MIRV.JPG This is a Minuteman III re-entry test at Kwajilein. Its warheads were developed by people I've met. These are the signs I grew up with. I was surrounded by wilderness, always behind 10-foot hurricane fences, always with these signs posted every 500 yards. Beyond them was unexploded ordnance and other stuff. This is Omega West. If you took a right at the bottom of the canyon, you got the skating rink and the reservoir. If you took a left you got guys in fatigues running at you with M-16s. ______________________________ I'm sorry you saw talent wasted on advertising and trading. Me? I was stoked the first time I talked to a guy involved in the Human Genome Project because it was the only project I knew of at the lab that wasn't directly or indirectly related to vaporizing Soviet children. I stand by my statement.

There's nothing new about this, though. David Ogilvie went from being one of the most important people in British intelligence to being the head of an ad agency. Isaac Newton spent his dotage trying to turn lead into gold. Graeber's article argues that technological progress is largely due to military competition: One of Graeber's larger points is that technology is a product of opposition. My larger point is that technology exists outside of opposition, and tends to kill fewer people in that case.On the other hand, I saw the best minds of my generation pour their talents into finding eyeballs for ads and and writing bots to trade castles in the air with each other...

It’s often said the Apollo moon landing was the greatest historical achievement of Soviet communism. Surely, the United States would never have contemplated such a feat had it not been for the cosmic ambitions of the Soviet Politburo. We are used to thinking of the Politburo as a group of unimaginative gray bureaucrats, but they were bureaucrats who dared to dream astounding dreams. The dream of world revolution was only the first.