How do you reform an agency authorized to use force? With more force, of course! (Though we still affirm that coercion is wrong, naturally.) Hubski is my primary source for depressing stories about law enforcement in the United States. I can't find a positive sentiment about police, it's all pigs, all the time. Instead of "rentacops are the only cops," how about weighing the pros and cons of possible alternatives? The alternative doesn't have to be perfect to be an improvement, if the current arrangement is as bad as it appears. The alternative might not be a good fit for every situation, but it might work better than expected in surprisingly challenging places. If we can't have a discussion, we can at least have a few laughs... ...at the risk of being reminded that the other side of the joke isn't very funny.

Police forces are inherently violent, having been created to protect the Heroic Captains of Industry by keeping the rest of us in our place. The war on drugs, the specific issue we all pay attention to because "maybe we don't need cops at all" is way outside the Overton window, was entirely consistent with origins of policing in really being about suppressing black people and hippies.

So we agree that state-sponsored policing is problematic. I also agree that reform in the direction I advocate is not likely given the political climate. But widespread public acceptance is not a prerequisite for good ideas. Unconditional basic income is also probably outside the Overton window, as was universal healthcare at one point, and same-sex marriage and women's suffrage. Someone advocating for these ideas might have been seen as an impractical idealist, but the ideas are still worthy of discussion.

For what private policing looks like in practice, see Diego Gambetta's The Sicilian Mafia: The Business of Private Protection. I admit, it has the virtue of making whose interests are being looked after transparent, but I don't think that would be much of an improvement.

Looks like an interesting read, but this seems akin to saying "For what private pharmaceutical distribution looks like, don't go to a pharmacy, but check out the drug dealer scene." The Mafia is well-known for coercive methods and criminal behavior. The fact that they provide "protection" doesn't mean they represent what a business offering security services must look like.

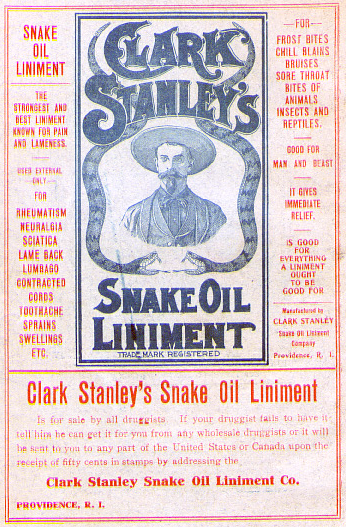

Stanley's Snake Oil was mostly mineral oil. When used to treat aches and pains, it was probably harmless if useless. You can still buy mineral oil at your local pharmacy; it is approved by the FDA for use in food and is sold as a remedy for constipation and irritated skin. About the time Stanley's elixir was found ineffective and removed from the market, Bayer's patent on aspirin expired, and authorities recommended it to relieve symptoms of those suffering from the 1918 Spanish flu outbreak. But the doses were well above what is considered safe today, and it is possible that aspirin overdose contributed to the unusual fatality rate of the pandemic. If someone were injured by snake oil today, they would have a number of recourses: · Demand a refund. · Leave negative reviews. · Enlist journalists to cover the story; the press loves a health scare. If these don't satisfy, there is the tried-and-true American approach of taking the quack to court for damages. Johnson & Johnson was recently ordered to pay $72 million in damages for selling talcum powder. Businesses providing remedies have a strong incentive to make sure their products are safe. Well, most businesses. Big Tobacco doesn't have to worry about any possible negative health effects of cigarettes, because they received perpetual immunity from liability in the 1998 Tobacco Master Settlement Agreement. Philip Morris et al. do have to send a bundle of money each year to the states to pay for tobacco-related health expenses and anti-smoking programs. Well, that was the idea anyway. Some states ran to the nearest payday loans storefront and sold off their claims to future payments as bonds. North Carolina took a different approach: "$42 million of the settlement funds actually went to tobacco farmers for modernization and marketing." So if you sell harmless snake oil to satisfied customers, the government will shut you down. If you sell poison, they might be willing to cut you a deal. What does the drug market look like post-regulation? In 1962, following the tragedy of birth defects caused by Thalidomide (which the FDA did not approve), rules were tightened to require proof-of-efficacy in new treatments. The benefit of the tougher rules is reduced risk that an ineffective drug will be widely used. The cost of tougher rules is that effective treatments are delayed while people suffer and die. After the change, the time to approval increased from seven months to thirty in 1967, and the number of new drugs approved decreased. Time to market is now measured in years, and is generally considerably slower than in Europe. A further irony is that, once a drug is approved for both safety and efficacy, it can be prescribed "off label" if doctors believe it will be effective for other purposes. This is a common practice and demonstrates that, in practice, we trust doctors to make decisions about treatments. One such treatment has been used since 1908 to treat tooth decay, and has been approved in Japan for decades. The FDA recently approved it as a tooth desensitizer for adults 21 and older, enabling dentists to use it off label to treat children with cavities. The stated purpose of the FDA is to protect the public health. But the incentives are different. "No FDA official has ever been pubicly criticized for refusing to allow the marketing of a drug. Many, however, have paid the price of public criticism, sometimes accompanied by an innuendo of corruptability, for approving a product that could cause harm." —Richard A. Merrill, former chief counsel for the FDAIn 1918, the US Surgeon General, the US Navy, and the Journal of the American Medical Association recommended use of aspirin just before the October death spike. If these recommendations were followed, and if pulmonary edema occurred in 3% of persons, a significant proportion of the deaths may be attributable to aspirin.

we know what the drug market looked like pre-regulation

You're presenting a lot of this data from the point of view of your conclusion, rather than taking into account each study individually. It seems to have given you the completely wrong impression of a lot of what you're talking about. -- Let's start with one of these: proof-of-efficacy Before the Kefauver Harris Amendment, companies did not have to prove their drug actually worked before selling it to patients. Which means that all you had to do was have a few trials that showed your drug didn't kill people and you'd have an opening to make hundreds of millions of dollars. Doctors simply don't have the time or expertise to evaluate the data on every drug put before. So if a drug is FDA-approved, and a company comes to them with a marketing report claiming 20% benefit over competitors, they won't double-check the methodology of the trial, the patient enrollment, the statistical tests. If the last set of treatments didn't work, they'll hop on the new drug until either (1) they see for themselves that it didn't work, or (2) an independent organization runs its own trial or checks patient records after the fact. So if that drug turns out not to cure disease X, you've exposed patients to unnecessary risk (and yes, all interventions carry risk), because the regulatory bodies would rather look in the rear view mirror to catch an accident. -- Take the conclusion of your figure: it's harder to get a drug approved when you require proof-of-efficacy The other outcome of the Kefauver Harris Amendment was a study to characterize the efficacy of all past drugs: DESI. They found that 3 in 10 drugs of those drugs didn't do anything. Say you had stage 4 melanoma, the doctors give you 6 months to live, and you're already looking at drugs that have a 10% chance of delaying your death. If you're going to pick one, do you want a 3 in 10 chance of picking the wrong one because the FDA was only there to make sure it didn't also give you a heart attack? -- There's trade-offs with every one of these regulatory decisions, but let's consider another example: off-label prescriptions This is a controversial solution to a problem of binaries. If a drug is good, a company can go through a full set of trials and regulatory approvals. But if that costs hundreds of millions of dollars, with a 1:3 chance of success, and the new market is smaller than cost * risk, they won't do it. So off-labels are a patch to the problem by saying: they won't run they trials, they can't market the drug. If a doctor doesn't have better options, they can prescribe the drug, knowing that it carries the lower grade label and increased risk. Some would say that's counterproductive, others would say a stratified landscape is better than a binary one. Your own link describes it as a polarizing term. It's a tough choice, but not really a reason against the FDA as a whole. And this isn't even starting to take into account fast-tracking drugs, FDA underfunding over the decades, fewer low-hanging fruit, etc. --"No FDA official has ever been pubicly criticized for refusing to allow the marketing of a drug. Many, however, have paid the price of public criticism, sometimes accompanied by an innuendo of corruptability, for approving a product that could cause harm."

I agree that I am giving one side of the argument; I think it is a side that gets less attention and should be included in a balanced discussion. Regulation has benefits and costs; alternatives to regulation have benefits and costs. When you say "There's trade-offs with every one of these regulatory decisions" you have expressed 90% of what I want to say. Trade-offs are almost inevitable in complex environments, and it's hard to make fair evaluations. I think there is a common tendency to over-value intentions rather than results, and to overlook large but inconspicuous effects. Mainly I find it fascinating to look into these subjects and learn what snake oil actually was, and that the FDA permits prescription-based homeopathic remedies for grave illnesses. Thank you for sharing your thoughts; in particular I had not heard of the Drug Efficacy Study Implementation.You're presenting a lot of this data from the point of view of your conclusion

This is true, though you elide the pressure in the other direction. The FDA, like every regulatory body that depends on specialized knowledge only available in the industry it's regulating, is subject to regulatory capture. It could only be trustworthy by having an antagonistic relationship with the drug industry, and that's not going to happen because those are the regulator's peers. The public is right to be suspicious of any decision favoring the industry that turns out to have been a bad one.The stated purpose of the FDA is to protect the public health. But the incentives are different.

Industry interference is a perpetual problem with regulating bodies, and the FDA is no exception. The FDA ‘Revolving Door’ Fosters Conflicts on Advisory Panels Conflicts of Interest at the F.D.A. But I wouldn't assume that the pressure is always in the opposite direction, helpfully reversing the overly conservative nature of the bureaucrats. Regulatory capture will tend to promote the interests of the most influential players. The giants in Big Pharma like Pfizer hope to make as much as they can from a new drug while patent protection applies. They can afford to wait a few years to collect. The biggest threat is not getting to market later, but that someone else will get a remedy to market first. Therefore, stifling competition is an important strategy. Maintaining high barriers to entry via an onerous approval process is a sound strategy. "If the FDA ceased to exist, the world would be a better place." I don't know if that sentence is true, but if I expressed it in a public place I would not expect to be taken seriously. But the evidence I have found points in that direction. I am sure we could find more with some effort, but so far the only downside mentioned to a lack of regulation is that a guy was permitted to sell some oil that probably did not cure any headaches. I think it's worth mentioning that he didn't wear a white lab coat; the "Rattle Snake King" had a circus act including killing a rattler and squeezing out the "oil" in front of an audience. At worst some people wasted money on snake oil when they could have gotten more relief from another treatment. Today we have an FDA to prevent charlatans from selling bogus remedies. Problem solved? Not exactly. "U.S. retail sales of homeopathic and herbal remedies reached $6.4 billion in 2012." The FDA restricts the sale of homeopathic remedies about as much as it restricts the sale of water, though this approach is being reconsidered. The current rules defer to the The Homœopathic Pharmacopœia of the United States, including the determination of which tinctures can be sold over-the-counter and which require prescription. Did you know that there are homeopathic treatments for cancer?